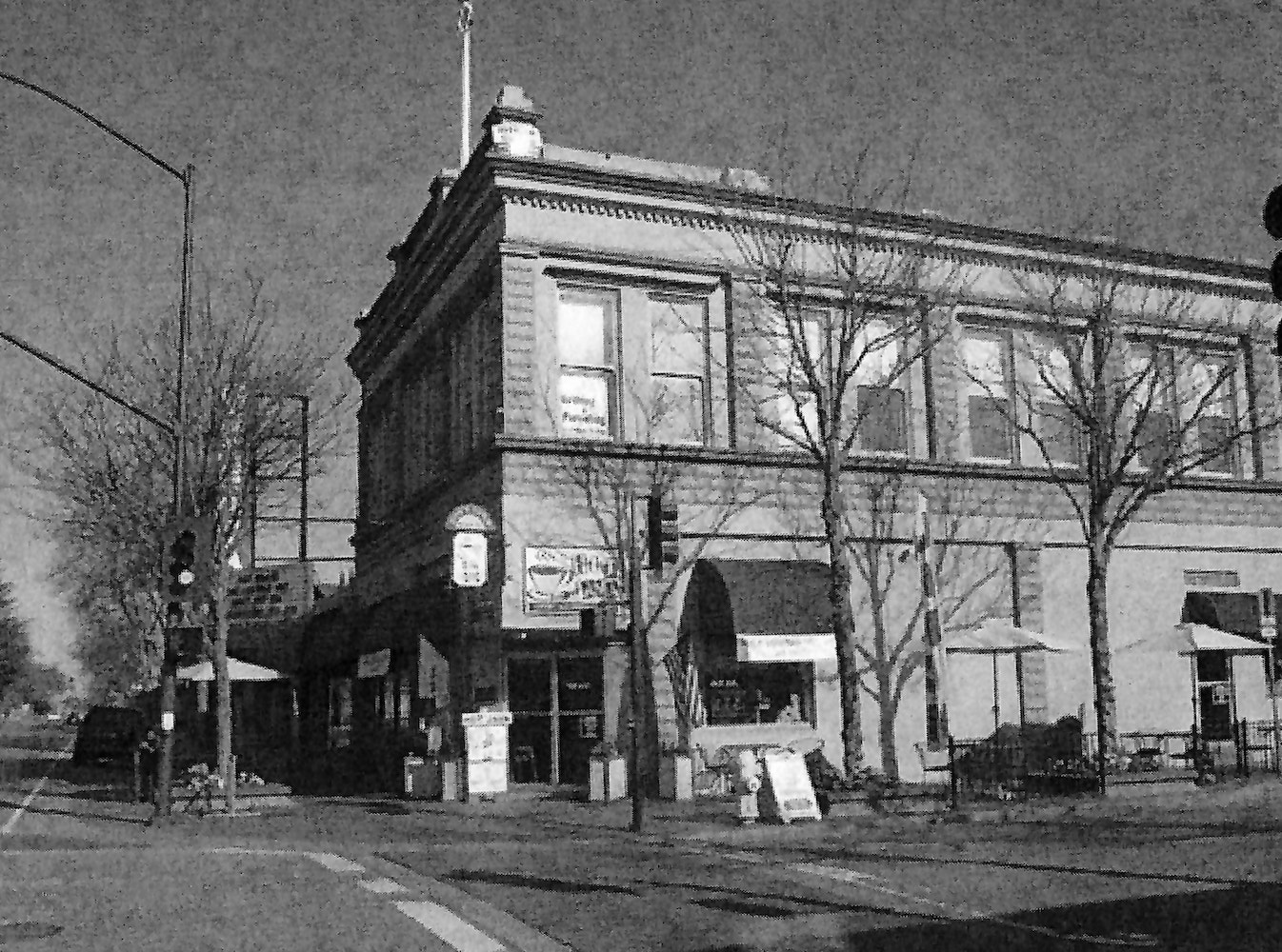

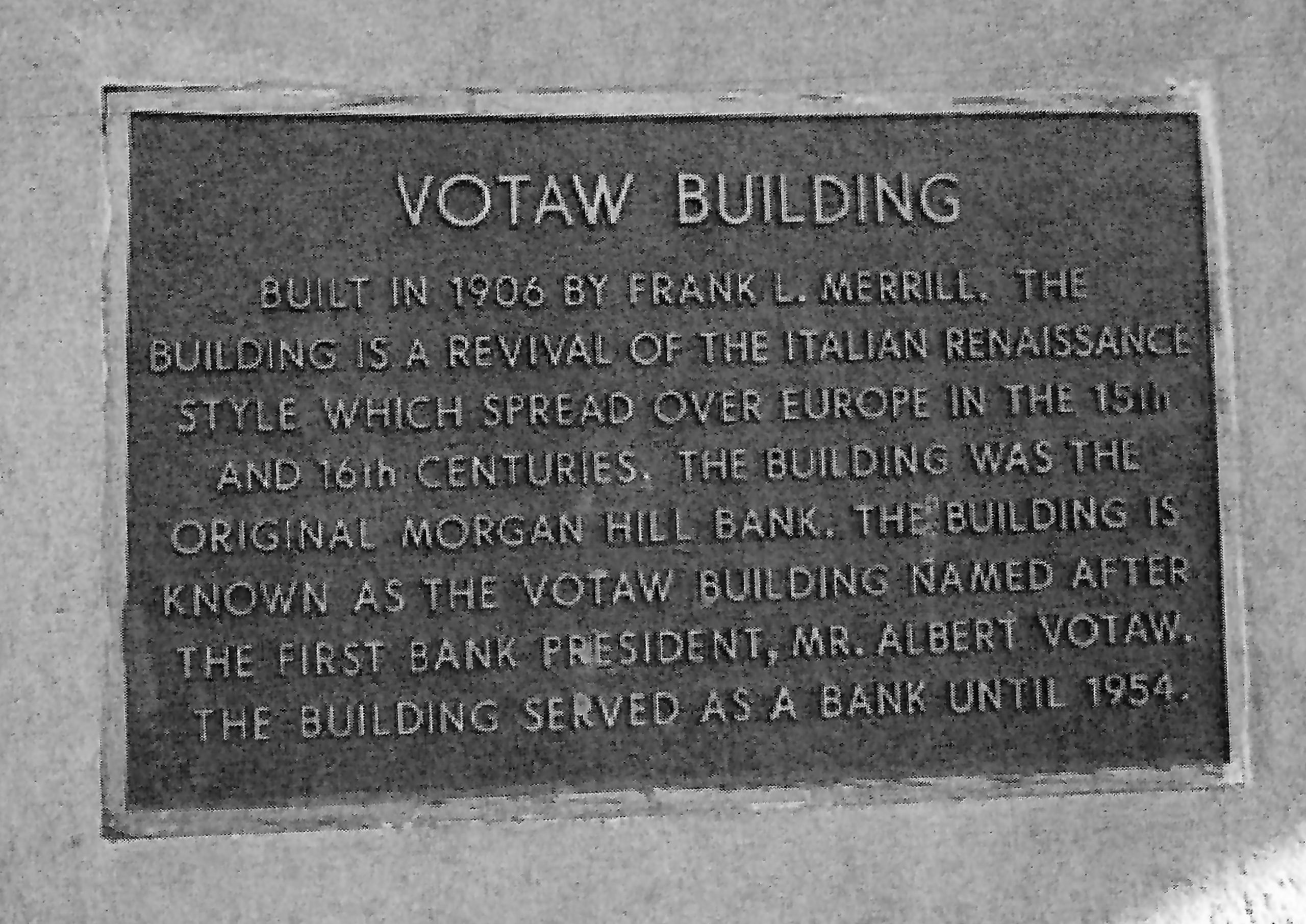

The Votaw Bank building in Morgan Hill, California. It’s no longer a bank, but a plaque on the wall (pictured below) tells its history. (Click on photos to enlarge them.)

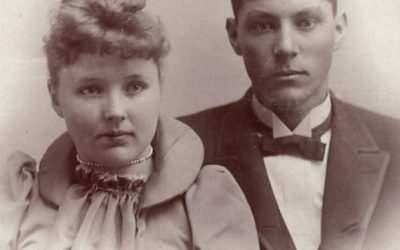

Elmer Votaw was born in 1869, and died in 1921 (age 52) from an illness that he contracted in Mexico, doing business there. His life was not long, but he had some impressive accomplishments.

On this page, you can read Elmer’s semi-autobiographical story, “Self Made Man.” You can also read the story of his business efforts in Mexico, written in 1965 by his son-in-law Will Boyce. These stories make interesting reading; Elmer’s life was full of amazing decisions and great ventures.

A brief timeline of Elmer’s life appears below.

- 1869 – Elmer’s birth (Oskaloosa, Iowa)

- 1891 – graduated from Penn College; married Ruth Smith, began farming on rented land

- 1896 – bought 200-acre farm in Iowa

- 1899 – bought 400-acre farm in Oklahoma

- 1904 – organized First National Bank of Cherokee, Oklahoma; was president for 1 year

- 1905 – moved to California and organized State Bank of Morgan Hill (scroll down)

- 1909 – moved to Wichita, Kansas and established the Mexico Immigration Land and Fibre Co.

- 1913 – moved to Whittier, California, and kept office in Los Angeles

- 1918 – Ruth passed away; Elmer married Grace Thurman

- 1921 – Elmer returns to Los Angeles and passed away from disease contracted in Mexico

SELF MADE MAN

Reared on an Iowa farm, by industrious, hard working parents; at the age of eleven, although quite small for my age, I found myself following a plow so heavy that it was impossible to lift it in place, so it was quite necessary that I drive the big horses around at the end in the proper place in order to keep my farrows straight. This was my beginning. From that day until twenty-one years of age, I knew little of life or the big world, but work, as the farm and stock call for constant care, consequently my school days were more or less limited, rarely going more than three months in the winter, remaining, as it were, between the plow handles the balance of the year. I sometimes remark to my children, now that they are graduating from the high school and one from college this year, that I graduated between the plow handles.

This life, with all its toil, had many a pleasant moment for the country boy, until at the age of twenty-two, I married and we two started life on rented land. Two horses, (one of them blind), one cow, one hog, and few chickens, a wagon, and a few second hand farming implements made up the outfit; with $90.00 in cash to run us through until the harvest. But happy we were for we had two strong hearts and four willing hands. Crops were only fair that season and after the last corn had been gathered in and hauled sixteen miles to market, where I could get five cents per bushel more that the near by market, I was fortunate in getting a winter’s job at $2.00 per day for myself and team, hauling corn to my landlords’ fatting cattle, which consisted of several hundred head, so that my job lasted well into February, then we moved to another rented farm, gaining little by little until at the end of the fourth year we had accumulated several head of stock, more tools for farming and about $500.00 in cash. In the meantime I had figured out that I was paying more rent to my landlords than the interest and taxes would amount to on the value of the average farm; land was increasing in value a little each year, and they were getting that also; therefore decided if I was able to find a farm for sale where the owner would sell for a small payment down and only wanted his interest, I would own a farm of my own. No sooner had I all this figured out, until I began searching about for what suited my ideas as a combination stock and grain farm. The right place was soon located in an adjoining county; 200 acres, half level prairie and half rolling pasture land with forty acres timber, fine for posts, fuel, and building material, just what the farm needed badly, The owner was an old gentleman who only wanted $1,000.00 cash and the balance, $5,000.00 might run five years at 6% per annum. A Six Thousand dollar farm, and my cash did not exceed Five Hundred dollars, but I wanted the farm, and set about to see what could be done. First went to my father, told him what I had found and that I wanted to buy the farm. Think of it! two hundred acres, $6,000.00, and me with $500.00. Of course he laughed at the idea and said I was crazy; that I’d loose all I put into it, and would not go with me to see the farm. Determined to buy it, I went to a good friend of ours who I knew some times loaned money, to see if I could borrow enough to make up the $l,000.00 to make the first payment. This I could do providing my father would sign the note with me, which he did after further talks on the matter and when he saw that I was determined to launch out on that 200 acres and in a way that would make good.

Two months later, in March, we moved twenty-five miles into the adjoining county on to our own farm, 200 acres, with $500.00 paid, the balance a debt. This however did not frighten me, before going I managed to pick up l9 all red, yearling heifers and one male together with about ten or twelve brood sows, going in debt for the most of these, also but this was my start. It would make this story too long to go into detail year by year, how we toiled early and late to make ends meet, but they met. Why? Because there was a determination to make good.

During the four years we owned this farm, there were many new improvements added, first, the house needed painting and a new front porch; a cistern for the wife; the old windless at the well was replaced by a new pump; the barn was remodeled, hog houses were necessary to save the young pigs; new fences replaced the old ones; the old orchard was reset with young trees; the entire farm took on a change and the neighbors wondered at the amount of work I turned off, and began fixing up their farms, so the entire community was in a degree changed for the better. A great deal of this improving was done during the winter months, so there never was a day that did not come with it some task that kept us employed. The results however, were quite encouraging. Besides meeting our interest and taxes, we had reduced the $5,000.00 mortgage to $3,000.00; and from two public sales of livestock made during the fourth year, we had a little more than enough to pay this $3,000.00; giving us for our four years work the farm clear of debt and considerable more stock after making the two sales than we started with.

But the $3,000.00 did not go to pay off the mortgage. I do not believe I am of a rambling nature, yet you may think so from the number of places we have lived and the different occupations pursued. Only when I see greater opportunities ahead, then I’m open f o r the advancement. So it was during the summer of that fourth year; I had been reading of Oklahoma with all its advantages for the young man with the grit and courage. Becoming so much interested, I determined to see that country, then a territory.

As soon as the crop was gathered, one morning in the early fall, wife and I with our three babies, bought our tickets for the southland; she stopping with the children to visit relatives in Kansas while I explored the plains of Oklahoma. After spending less than a week driving over what seemed to me to be the greatest country I had ever been privileged to see, and one in which I could see untold opportunities, I paid my $3,000.00 for 160 acres and started from Iowa.

Upon hearing what I had done, the wife, not knowing what a good class of people lived in Oklahoma, thought it would be awful thing to go down there among the Indians (?) so it was decided we would only rent our farm for one year and try it out. This was done, and we chartered a car, loaded it with household effects and two or three of my best teams and pulled out for Newkirk, Oklahoma. This was in January. We practically missed the experience of winter that year; the fall having been nice in Iowa and spring came so early, with all the beautiful, green wheat fields. We fell so completely in love with our new location, and surroundings that we traded our 200 acres in Iowa for 400 acres more in Oklahoma, mostly in wheat, and that year we harvested 6,300 bushels of wheat. This move was another beginning for me in finances, and greater opportunities loomed up before me.

The Iowa farm was valued in our deal at $50.00 per acre, $20.00 per acre or $4,OO0.00 more than we had paid four years ago, taking in the Oklahoma land at $38.00 per acre. After harvesting two large wheat crops, I sold the 4OO acres at $55.00 per acre cash. I was then, ten years after starting with $90.00, able to write my check for $20,000.00.

For the next four years, I bought and sold many farms and became interested in organizing the First National Bank at Cherokee, Oklahoma. Being elected President of this bank, it became necessary to move from the farm to take up new duties. By the end of the sixth year in Oklahoma we again saw greater possibilities ahead; selling our farms and banking interests, we came to California with $35,000.00, where I again entered the banking business, organizing a state bank and successfully managing that as the President for four years, when we were again approached by a banker to sell. Having already become interested reading of the great opportunities in Old Mexico, I decided before making a change this time to go over into Canan and view the land. Finding even more than I expected and believing I had this time found the place possible to make a real fortune, I selected 12,300 acres of choice, rich land in rich Old Mexico, and returned, selling our bank and other interests this time for about $50,000.00 and purchased the land. Seventeen years now had passed since we rented our first little farm.

My next work was not to organize a banking company, but a land company to colonize the 12,300 acres in Mexico. In this purchase I had obligated myself for a sum far beyond my ability to pay, without making it out of the reselling of a portion of the land. Knowing little about the colonization business and especially in Mexico, I contracted with two friends (supposedly) whom we will call Smith and Jones, to help me in this new venture. They contracted to meet their share of the payments. Time went on. The land company was organized with myself elected to be its President and General Manager; an office was rented, equipment and literature supplied. I had full charge at the new game for me, but I felt sure we would soon make a bushel of money, for my two helpers, Smith and Jones were both educated and experienced, I had some money and the same determination to make good in this.

All hands set out to colonize and establish one of the most thrifty American Colonies in Mexico. A campaign for selling land was put on. At the end of three months I had about 26 agents working under me, we were operating a special car to Tampico, Mexico, taking land buyers by the score. All went well for awhile and we were making money, then the war clouds began to appear, a condition over which we had no control; there came also the payments on the land. Smith and Jones who had promised so faithfully to put our project through could not meet their part. Nothing invested, they had nothing to loose. I had personally made the initial payment. Even with our successful start, the cash in our treasury was not sufficient to meet the payments and take care of other expenses. Something must be

done, I had never failed and could not now. My property consisted of farms and other real estate on which we could not realize cash. I went to a banker and asked for $12,000.00, this I got by placing my personal property up as security. I was into it now and going deeper, for the interest was counting rapidly; my friends said I’d loose all I had. True it did look bad, as the warring conditions grew worse month by month, and this checked our immigration business. Those who had already bought land became discouraged and began to fail in their payments. This put our company in bad shape, with the interest and other approaching payments that we knew would be impossible to meet under those conditions. We hoped and prayed that the troubles in Mexico would cease, and give us a chance. Instead of better times below the border, it grew darker and the time came when we must face another payment. Smith and Jones having nothing invested in our enterprise went back to the school room for a living, leaving me to fill my place as Manager and meet the Company’s obligations alone.

I have always been of an optimistic nature, knowing nothing of defeat. I saw in this land a fortune, as I did when buying, it two years before; all I asked was a condition in which to handle it and carry out my plans. I had a family of seven to feed; children to clothe and send to school and the oldest must go to college. Really hard times had come to the once prosperous farmer and banker; my all was planted in Mexico, and I must make good for my friends were watching me, prophesying I would loose all I had, and saying I had better staid in the United States. While everything I had except the home was mortgaged to the limit, yet my credit was gilt edged, and I was determined to stay with this and make good. With this determination, I bought a ticket for Iowa and laid the whole matter before an Uncle who had money and confidence in my judgement, as I had previously made a number of deals for him that had made him good money. The result of this trip was, I came back with about $10,000.00 and my Uncle was a stockholder in our company.

In short, we have fought faithfully, this fight, all through the troublesome times in Mexico, and held our land. This however has been done at a great sacrifice of my own property, but having encouraged my Uncle and others to invest in the project with me, I was more determined than ever to bring the company’s affairs through to success, that each stockholder might receive a profit on his investment.

I have the honor, as President and General Manager of our Company, of recently signing a contract to sell $200,000.00 worth of our Mexico land to an oil company, which crown our efforts with success even in this, the handling of Mexico lands, notwithstanding the country has been for the past five years in a war that put all odds against us.

Our next venture will be to organize and drill for oil on what we yet own below the border. We hope this to be our greatest achievement and success, and feel that it will be, as I am but in middle age and past experience has fitted, now for a real successful career through life.

In conclusion wish to say: I would be pleased to meet the members of the “Get-Out and Get-On Club” and encourage someone who may think his road to success is harder than the other fellow’s. Such an organization certainly has a useful place among men and should be the means of landing many a man at the

top with success.

E. J. Votaw

Los Angeles, California

ADVENTURE IN EXPLORATION FOR OIL IN MEXICO

In 1909, E. J. Votaw and associates purchased some 12,300 acres of land lying between Lake Tamiahua and the Gulf of Mexico. The intent was to open for sale to United States Citizens a large agricultural subdivision. For purposes of proof and demonstration of the suitability of the land for profitable cultivation and settlement the company, given the name “Mexico Immigration Land and Fiber Company”, set up a sort of pilot demonstration by clearing away the jungle from a fairly large tract of land and planting it to pineapple, sugar cane, fiber producing plants, and grain. Cattle were also brought in and allowed to forage for themselves, on the lush growth of the jungle.

The decision to abandon this project, at least temporarily, was prompted by two events: One, the agricultural project had little more than begun when a roving band of soldiers of the Revolution moved in and took possession. The manager, Albert Votaw, brother of E. J. Votaw, and his wife were driven off, their residence was taken over and the cattle were slaughtered for food. Temporarily the American owners and operators were totally dispossessed. The second event was an exciting wild-cat oil project on Idlo Island which was almost directly west of the Mexico Immigration Land and Fiber Company property, about three miles across Lake Tamiahua. Coupled with this was the alleged finding of oil seepages on the Gulf side of the Company’s land. The evidences strongly suggested the possibility of oil bearing sands on the property. In comparison with oil production, agriculture lost its appeal.

E. J. Votaw, President, manager and principal owner of the property was keenly aware of the enormous cost of the wild~cat oil exploration. Yet, he was eager to develop his own company. The one way to finance such undertaking was to capitalize the newly discovered oil prospects and sell the northern half of the land holdings. He found a prospective buyer in Edward Doheny, second only in oil production and refinement to the English firm, El Agula, A sale was negotiated at a price around thirty to thirty‐two dollars an acre – total price of $200,000.00. The contract was committed to escrow.

Before finalizing the escrow, Doheny was called on business to New York City. Meantime the volatile politico-economic naturalization issue took a more threatening turn. Doheny, who allegedly had found it much more profitable to bribe the officials than to obey the laws, had become a controversial figure. Already he was apprehensive of the determined governmental opposition. Eventually he and his oil enterprises were driven out of the country. The up-shot was Doheny refused to sign the escrow contract.

E. J. Votaw was not a man to easily give up. He decided to promote an oil company and, under contract with the Mexico Land and Fiber Company, explore the ranch for oil. The company, he named Port Lobos Oil Company, succeeded in raising money by the sale of stock sufficient to finance the initial steps of operation. These included the construction of living quarters for a small crew of employees and living and office accommodations for the manager. A drilling site was selected, a wharf built and a roadway established. The Land Company had previously constructed a modest residence and utility buildings. These were occupied by Mr. Duncanson, manager of the property following the withdrawal of the soldiers. The manager had free use of the residence and the ranch and acted as liaison agent for the owners in the United States. He was a loyal friend of the company and could easily communicate with the Mexican people.

Apparently the drilling site was selected personally by E. J. Votaw. At least no geologist was employed other than the original Mr. Cummings. He had not been used in connection with the initial planning and drilling.

For this preliminary work E. J. Votaw, accompanied by his wife, Grace Thurman (second wife, his first wife having passed away in 1918), took charge, personally. During President Votaw‘s absence beginning March 1921, the office force was Vice President John Cave, Vernon Votaw, the eldest son of E. J. Votaw, and a secretary. There were salesmen in and out of the office, one of whom was an attorney named Youngdall. He was enthusiastic about the project and was used for legal advice, through not retained. Before E. J. Votaw left the States, he found a man who seemed to have the right qualifications for managing this lonely wilderness job of hiring and supervising a drilling crew. While he had no experience in oil production, he was a retired army Colonel and experienced in managing men. Moreover, both he and his dynamic wife were enthusiastic about the adventure. This was Colonel Thornberry.

Votaw’s confidence in the project and his integrity in management were demonstrated by the commitment of himself and his family in personal supervision and unremunerated physical labor.

Minimal building requirements were a combination residence and office, a mess hall, and a rooming house, called “bedago” for the laborers. These buildings were shipped pre-fabricated from Tampico and constructed on the site, under the supervision and by the labor in part of Votaw himself. Furthermore, while his son, Vernon, was the main strength of the office in Los Angeles, his son Clayton and wife came early in June and spent the summer months, 1921, on the job.

Clayton engaged in every phase of construction: foundation, flooring, erection, plumbing, roofing. Even the two younger sons, Harold and Howard, were present a part of the summer and found work suited to their age. It was no small sacrifice for E. J. Votaw and wife, and for Clayton Votaw and wife to leave their comfortable homes in California and set up housekeeping on the edge of the wilderness with only hard labor to beguile the sixteen hours left after eight hours sleep.

After about six months of strenuous mental and physical labor, President Votaw returned to his home in Los Angeles. He was a sick man. Eager for first‐hand reports on office operations he forced himself to go to the office the day after his arrival. Following a conference with his son, Vernon Votaw, John Cave, and others he made a start on clerical matters, dictated one letter but found it impossible to apply himself further. He returned to his home and a few days thereafter he passed away, a victim of fatigue and amediasis, endemic in Old Mexico.

The Port Lobos Oil Company was at a critical stage, construction, materials and the planning for drilling had been accomplished, application had been made for a drilling permit, a field manager had been employed; but the originator, manager, and genius of the enterprise was cut off in his prime, leaving a terrible void. There was no one qualified to take up the tenuous situation of leadership and management. John Cave, vice-president was willing and ready to assume the duties of president but obviously was not suited to the requirements. He had no knowledge of the oil business and only a superficial acquaintance with the affairs of the company. Furthermore, he did not have the confidence of the Votaw family and its close associates in the enterprise. Actually there was no Board of Directors. While Port Lobos was a legally constituted business in which many individuals were represented, it was governed by its president and associates selected by him.

Because of the youthfulness of his sons, E. J. Votaw had named his son‐in‐law, William T. Boyce, as Executor of his estate. In the dilemma that the company faced, the family and associates turned to Boyce with an urgent request that he accept the office of President of the company. This meant to take leave of absence from the office as President of the Fullerton Junior College and give full time to the fledgling enterprise. Boyce yielded to the request with the greatest reluctance for he was fully aware of his lack of qualifications for the job. He had only conversational knowledge of the company and no background of experience in business adminiStration. Three problems had the highest priority:

Obtaining the cooperation of the vice‐president who was crushingly disappointed in not being selected as president.

Obtaining the drilling permit, the lack of which was a growing threat to the confidence of stock holders.

Obtaining managerial results from Colonel Thornberry.

Boyce’s first act was to send Thornberry, accompanied by his wife, to the Aqua Dulce properties. There he was to carry on where the late president had left off in preparation for drilling the first well; also and most importantly, to relentlessly press for the drilling permit. Weeks aggregating months passed with no permit. Thornberry was requested to go to Mexico City to make a personal appeal to the highest authorities. He did as requested, but met only evasions. In disgust, Thornberry decided to return to Los Angeles. Boyce knew that for him to come back, only to report defeat would bring an avalanche of disappointment and lack of confidence. The outcome would be disastrous to the company which was dependent upon the continuous sale of stock to finance drilling operations. In something close to desperation, Boyce decided to go to Mexico. He telegraphed Thornberry not to return to Los Angeles but to stop in El Paso and await Boyce’s arrival.

Boyce met Thornberry in El Paso and they took the first train to Tampico. After a few days in Tampico, consulting with men of influence, some of whom he was introduced to by Thornberry and others with whom the late E. J. Votaw had established friendly and cooperative relations, the two men proceeded to the ranch.

Travel was by a slow freighter requiring a night and half‐day to make the journey down the canal and the lake to the ranch. Sleeping accommodations consisted of a board deck, the open sky and the steady “chug-chug” of the engine. The old soldier slept in apparent comfort; Boyce shifted from one segment to the other of his horizontal circumference until every peripheral joint was in pain.

Upon arrival the two men immediately took up residence in the already cockroach‐ridden headquarters. Boyce had long talks with Duncanson, who knew the characteristics of Mexican officialdom, but nothing of oil production or exploration. He took Boyce to the Gulf Coast in his small truck. While on the beach they picked up a load of oil-soaked sand patches. These Duncanson used for road‐paving. Duncanson thought these oil patches came from oil seepages in the off-shore. However, Boyce observed steel piles several hundred yards from the shore line, which were used to fasten hawsers of oil tankers while being loaded with oil through a pipe line connected with a distant oil field. To him it seemed probable that the oil which soaked the sand came from waste oil in loading operations. Duncanson claimed that oil seepages along the shore had been found from time to time, that a seepage covered by shifting sand could be permanently lost to view.

Boyce decided that it was necessary to travel to Tuxpan, capital of the state of Vera Cruz, and seat of the State’s authority in matters pertaining to the exploration of mineral and petroleum lands. The first stage of the journey was made in a jitney, driven by a native. There was no language communication; also there was no road. The automobile was driven on the wet sand off the Gulf. On arriving at the inlet connecting Lake Tamiahua with the Gulf the first leg of the journey ended. Transportation across the inlet was in a dugout paddled by a native. Another jitney picked up his passenger and the trip on the wet sand continued to the El Agular oil plant on the Tuxpan River. In all this distance requiring three or four hours of travel only three men were seen, the two jitney drivers and the boatman.

The next stage of the journey was on a passenger boat up the Tuxpan River. The boat was fairly loaded with gay and friendly people, but no one who could speak or understand English. Arriving at the city of Tuxpan a hotel was soon found. The lobby was on the first floor, but all rooms were at second-floor height, supported by posts, tree trunks, for what purpose Boyce could not ascertain. It certainly was not for stability, for the building swayed and creaked with the movement of guests down the outside walk to and from their rooms.

Having succeeded in making the desired contacts and in securing the proper signatures to official papers, and having been assured that there would be “no further delays”, Boyce returned by the way he had come, feeling that the gordion-knot had been cut.

Further contacts were made in a visit to an oil field belonging to the Doheny interest, and also to Idlo Island. Boyce now returned to Tampico, reported the results of his trip to Tuxpan to interested parties, then left by train for Los Angeles. The return trip was uneventful except that the Mexican train was derailed by a washout from a heavy rain. The engineer was killed and there was a long wait for an auxiliary engine and coaches to resume the journey to El Paso.

Soon after Boyce’s return the permit was received and Thornberry was ordered to proceed with drilling of a well. Now that the permit had been granted and drilling operations begun, the salesmen found a fair demand for the companies stock. This flow of capital made possible uninterrupted operations.

At about 3,000 feet an oil sand was tapped but the flow was too meager for profitable production. The decision was to go deeper. At about 4,200 feet the drilling tool was lost. Weeks were spent in futile efforts to recover it. The painful decision to drill another well was a crushing experience, but it was the only alternative to quitting.

At this juncture either the driller was dismissed or resigned and for the next several weeks operations were at a stand still. Boyce was able to persuade a friend, O. A. Kreighbaum, an experienced and highly reputable oil driller in Fullerton, to go to Mexico and take full charge. Kreighbaum was a fine citizen. He had served on the Fullerton Junior College Board for six years, during which time Boyce was employed as a member of the teaching staff. His acceptance meant a resignation from the company in which he had been employed for several years and it meant separation from his home for an uncertain length of time. Thornberry‘s service having been discontinued, he returned to the States.

In September, 1922, Boyce’s leave-of-absence was to expire and he wished to return to his professional occupation as originally intended. Meantime, a resident of Whittier, James Thompson, an Englishman and experienced business executive had become enthusiastic about the company and had invested several thousand dollars in its stock. He had recently been appointed to membership on the Board of Directors. Thompson was easily persuaded to assume the office of President, as successor to Boyce.

While Thompson was the nominal President, the main force and manager of the company was Vernon Votaw, eldest son of the late E. J. Votaw. He had already proved to be a most resourceful and energetic promoter and guardian of the interest of the company. He did everything humanly possible to keep the company alive, to explain the facts with which the company was faced and to protect the interest of every one connected with the company as investors or officers, in so far as it was possible.

President Thompson also applied himself in devotion to the needs of the company, especially to the goal of completing the second well. However, the going become increasingly difficult. Kreighbaum encountered long delays, employees quitting the job, and finally the resignation of the head man of the Mexican force. Disgusted and longing to return home although still confident of the prospect, Kreighbaum requested permission to resign without prejudice.

Then came the death blow. The Mexican Government invoked its constitutional right and enacted a law which established a frontier and sea coast zone in which the mineral rights belonged to the government and foreigners were excluded from ownership. The zone encompassed the entire Aqua Dulce Rancho. The legal action stemmed from an old Spanish doctrine, which had been from time to time enunciated by the government, since the early 18th century.

Specifically, the Mexican Constitution of 1917 declared that petroleum deposits belonged to the State and did not go with ownership. Many attempts had been made to enact legislation under this constitutional provision, but up to this time, foreign operators protested through their home governments on the grounds that such action would be ex post facto. Now under the strong leadership of President Abregon, who was a political product of the revolutionary era, the old methods of opposition were to no avail.

The owners and backers of Port Lobos Oil Company were confronted with a choice of one of three courses of action:

They could consolidate their interests and wait for a more favorable attitude of the Mexican government. To do this the annual property tax, which had become a heavy levy on 12,000 acres of land, would have to be paid. Also the company would have to share in the cost of negotiations by the companies who sought compensation. Actually no individual or corps of individuals was prepared to assume such expenditures which at best were a gamble.

They could strive to interest some individual or company in buying the property and taking the chance of a favorable settlement. But to seek was alas! not necessarily to find.

They could accept as inevitable the loss as a fact accomplished and strive to explain to all concerned that the unhappy outcome was the result of the arbitrary action of the Mexican government, by which the large companies as well as the small had been dispossessed.

Neither of these steps was formally taken. James Thompson held on to his Presidency long after Port Lobos closed its office. He was the President of a defunct company but he bravely fought to find some way out . Actually he and the others who shared the heart‐break followed the third alternative, but the action was not finalized by any action, formal or legal. The Port Lobos Oil Company just died and faded into oblivion.

The loss to many small stockholders was a cause of grief to all who at any time held an office of responsibility in the company. The E. J. Votaw family suffered a staggering loss. E. J. Votaw had even borrowed to the limit on his life insurance. Many friends and close relatives lost all that they invested in the company. The losses extended to those who had ventured to buy the acreage in the beginning.

In retrospect the risk was too great for a new company with assets so limited as those of the Port Lobos Oil Company. Large scale speculation has its place in the private enterprise system, but the risk should not be taken by those who cannot afford to take a loss.

The only comfort that could be extracted was the knowledge that at no time did the promoters attempt to bribe or by-pass the Mexican government, nor was the money raised by sale of stock as the result of false representations, issued officially. There were strong and persuasive evidences to support the belief that the land was a potential oil field. And it is possible that had a well been drilled to greater depths oil would have been found. Forty-two hundred feet was not sufficient for a definitive test.

After years of diplomatic negotiations, financed by the major foreign companies whose properties had been confiscated, a settlement was made by which the companies recovered a small portion of their losses. How much is not known to this writer. One thing is certain the settlement by the Port Lobos Company even if it had been able to bear its share of the expenses incurred in the long diplomatic and legalistic battle.

William T. Boyce 3/05/65

Elmer Votaw Biographical Record

E. J. VOTAW. The Mexico Immigration Land and Fibre Company, which has for its purpose the subdividing of land and the establishing of an American colony in the northern part of the state of Vera Cruz, Mexico, was organized in Wichita, Kans., by E. J. Votaw, and incorporated under the laws of the state of Kansas, with a capital of $300,000, the other officers of the company being I. T. Giles, vice-president, and E. L. Foulke, secretary and treasurer. The officers and directors of the company are themselves financially interested in the enterprise and in seeing the colony assume a leading place both as a city and as a fruit-growing district on the east coast of Mexico, where they have purchased twelve thousand acres near Tampico.

The climate of that section of Mexico where the colony is situated is well adapted to the production of tropical fruits as well as many kinds of vegetables, the even rainfall throughout the year supplying the necessary moisture for the growth of the crops, irrigation being rendered unnecessary by the unfailing supply of water found at a short distance from the surface of the ground. Excessive heat, as well as heavy storms or winter weather, are unknown in this district, and the rich soil is proving all that could be desired for the raising of such fruits as bananas, oranges, lemons, limes, grape fruit and pineapples, from the last named of which fruits the American colony takes its name, Pineapple City. The raising of cane for making sugar is also a thriving industry of the new settlement, and Mr. Votaw, besides being president of the Mexico Immigration Land and Fibre Company, is vice-president and general manager as well of the Pineapple City Sugar Company, the home offices of which are located in the Marsh-Strong building, at Los Angeles, Cal., where Mr. Votaw established his headquarters in the year 1913. The oil interests of that section of Mexico where Pineapple City is situated must not be overlooked, it being in the center of what is bound to become a most active oil field, one of the world’s greatest gushers being located a little to the south of it, and the development of oil on the property of the company is in the hands of a man thoroughly competent in every respect to deal with the enterprise, while to Mr. Votaw’s brother has been given the charge of the agricultural work of the colony.

Previous to his interests in Mexico, E. J. Votaw had been engaged in the banking business, his first experience in that line of business having been the organizing in 1905 of the First National Bank of Cherokee, Okla., of which he was for a year the president, at the end of that time selling his interest and buying out the Cherokee State Bank, of which he was both president and manager for a year. Removing to Morgan Hill, Cal., he then organized the State Bank of Morgan Hill and was for about four years its president and manager. He then sold his interests there, and went to Wichita, Kans., where he established the Mexico Immigration Land and Fibre Company, after which, in 1913, he came to Los Angeles, where he has made his home ever since.

Born near Oskaloosa, Iowa, on December 16, 1869, Mr. Votaw was the son of Joseph Votaw, and received his education at a district school and at Penn College, Oskaloosa, Iowa, until the age of twenty-one, at which time he engaged in farming until 1905, the year in which he entered the banking business. His marriage to Ruth A. Smith took place in Oskaloosa, on December 31, 1891, and they are the parents of five children, namely: Vera M. and Vernon J., both of whom attend the Friends’ College at Whittier, Cal.; E. Clayton, a student in the high school; and Albert Harold and Joseph Howard Votaw, who are pupils in the public schools of Whittier, of which city Mr. Votaw is a well‐known and valued resident.

This biographical information was published in “A History of California” Vol. III, published by Historic Record Company, Los Angeles, 1915.

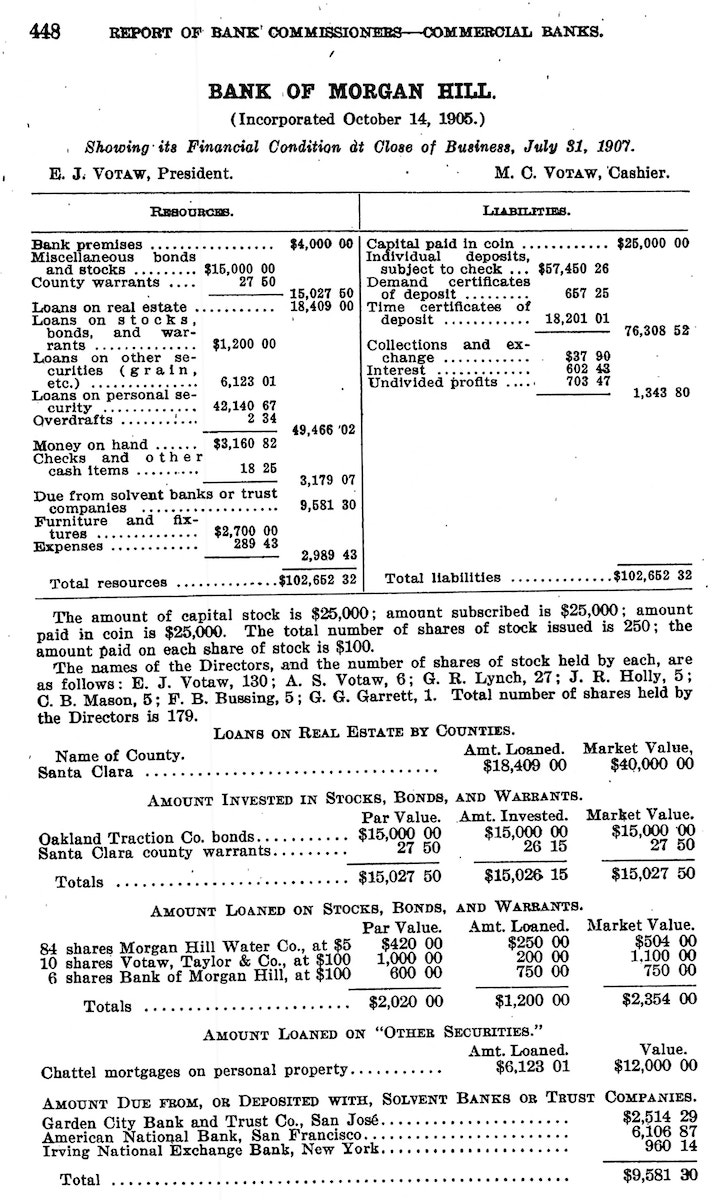

Above is a financial statement for the Bank of Morgan Hill, published in 1907. It shows that Elmer (E.J. Votaw) was president of the bank, contradicting the plaque on the bank wall (pictured above on this page).

The Marsh-Strong building in downtown Los Angeles was (beginning in 1913) the site of Elmer’s office for the Point Lobos Oil Company.

0 Comments