Jamie is just about to publish one of his projections. I know, because I saw his not-yet-finished piece backstage at the league website. I am pretty excited about it.

In fact, I can’t wait for him to put the finishing touches on it. So I am going to post the entire thing here, as it stands at this moment , so no one has to wait :

First things first, I have to hand it to Ron – few people can create a spreadsheet like Ron can create a spreadsheet.

Isn’t that great stuff? Nice, quick, straight to an outstanding point nobody should overlook. Exactly what we need from posts on the website.

Except now, when we have to pay attention to the ugly side of our league, where people are suffering from losing (and the anticipation of losing.)

Let’s review some history. Back on Saturday, basking in the glow of what I thought might have been the best Wolverine spring drafts in a decade, I posted a prediction of how our teams would do this season based on Fangraphs Depth Charts projections. It’s top few lines looked like this:

|

TEAM |

OFF WAR |

PIT WAR |

TOTAL WAR |

Wins |

Losses |

|

|

Wolverines |

30.5 |

21.2 |

51.7 |

|

100.7 |

61.3 |

|

30 |

21 |

51 |

100 |

62 |

||

|

27.7 |

21.7 |

49.4 |

98.4 |

63.6 |

||

|

Tornados |

25.7 |

21 |

46.7 |

|

95.7 |

66.3 |

|

Kangaroos |

30.2 |

15.3 |

45.5 |

|

94.5 |

67.5 |

|

22.9 |

21.7 |

44.7 |

93.7 |

68.3 |

||

|

21.2 |

21.4 |

42.6 |

91.6 |

70.4 |

||

|

Balk |

26.8 |

14.9 |

41.7 |

|

90.7 |

71.3 |

|

25.8 |

15.6 |

41.4 |

90.4 |

71.6 |

||

|

28.5 |

12.7 |

41.2 |

90.2 |

71.8 |

On Sunday, after fixing a few glitches, I posted the same spreadsheet again, showing the W’s had slipped just a little:

|

TEAM |

OFF WAR |

PIT WAR |

TOTAL WAR |

|

Wins |

Losses |

|

30 |

21 |

51 |

100 |

62 |

||

|

Wolverines |

29.4 |

21 |

50.4 |

|

99.4 |

62.6 |

|

27.7 |

21.7 |

49.4 |

98.4 |

63.6 |

||

|

Tornados |

25.7 |

21 |

46.7 |

|

95.7 |

66.3 |

|

23 |

21.7 |

44.7 |

93.7 |

68.3 |

||

|

Kangaroos |

30.2 |

14.2 |

44.4 |

|

93.4 |

68.6 |

|

21.2 |

21.4 |

42.6 |

91.6 |

70.4 |

||

|

25.8 |

15.6 |

41.4 |

90.4 |

71.6 |

||

|

28.5 |

12.7 |

41.2 |

90.2 |

71.8 |

||

|

Balk |

26.7 |

14.1 |

40.8 |

|

89.8 |

72.2 |

|

Dragons |

24.6 |

16 |

40.6 |

|

89.6 |

72.4 |

|

Pears |

24.7 |

15.6 |

40.3 |

|

89.3 |

72.7 |

But, you know, it was nice seeing the Dragons and Pears almost catching the Balk, and the W’s were still 3.7 games ahead of the T’s.

And on Monday, I posted a spreadsheet that stuck way off the right side of your screen. Based on Baseball Prospectus ratings of individual players in 5 tiers, giving top-tier players 5 points and bottom tier players 1 point (and unrated players, which is most of them, 0 points), the Wolverines came out on top with 53 points to the Tornados’ 51. (Actually, there was an error in that report, and the W’s really had 55 points).

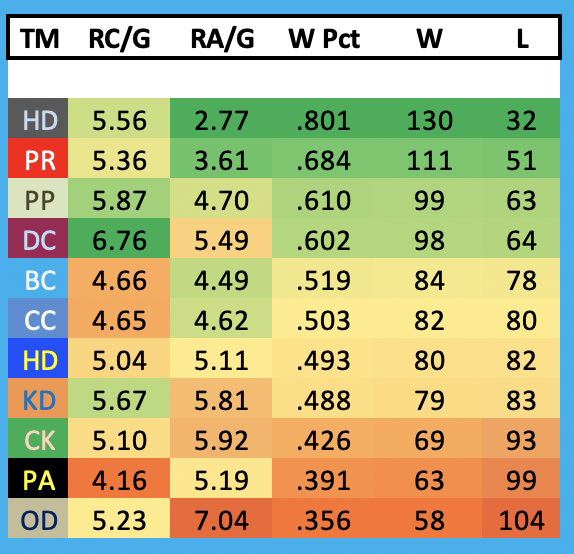

Then on Tuesday I published this dreadful thing, projecting our season records based on our players’ spring training stats:

|

TM |

RC/G |

RA/G |

W Pct |

W |

L |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

FH |

5.56 |

2.77 |

.801 |

130 |

32 |

|

PR |

5.36 |

3.61 |

.684 |

111 |

51 |

|

PP |

5.87 |

4.70 |

.610 |

99 |

63 |

|

DC |

6.76 |

5.49 |

.602 |

98 |

64 |

|

BC |

4.66 |

4.49 |

.519 |

84 |

78 |

|

CC |

4.65 |

4.62 |

.503 |

82 |

80 |

|

HD |

5.04 |

5.11 |

.493 |

80 |

82 |

|

KD |

5.67 |

5.81 |

.488 |

79 |

83 |

|

CK |

5.10 |

5.92 |

.426 |

69 |

93 |

|

OD |

5.44 |

6.52 |

.410 |

66 |

96 |

|

PA |

4.16 |

5.19 |

.391 |

63 |

99 |

Then on Wednesday, one of the two best players on my team, Walker Buehler, coughed up 9 earned runs in 5 innings, which probably dropped the W’s into last place on the spring-training projection.

Then later Wednesday I heard that Eloy Jimenez, maybe my second best offensive player, had hurt his shoulder.

Then today three of you helpfully informed me, as a preamble to trade proposals, that Jimenez would be out up to 6 months waiting for a torn tendon in his shoulder to heal.

When you add Eloy’s injury to Walker’s melt-down (and ignore everything else that happened at spring training since Monday), here is what you get:

|

TM |

RC/G |

RA/G |

W Pct |

W |

L |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

HD |

5.56 |

2.77 |

.801 |

130 |

32 |

|

PR |

5.36 |

3.61 |

.684 |

111 |

51 |

|

PP |

5.87 |

4.70 |

.610 |

99 |

63 |

|

DC |

6.76 |

5.49 |

.602 |

98 |

64 |

|

BC |

4.66 |

4.49 |

.519 |

84 |

78 |

|

CC |

4.65 |

4.62 |

.503 |

82 |

80 |

|

HD |

5.04 |

5.11 |

.493 |

80 |

82 |

|

KD |

5.67 |

5.81 |

.488 |

79 |

83 |

|

CK |

5.10 |

5.92 |

.426 |

69 |

93 |

|

PA |

4.16 |

5.19 |

.391 |

63 |

99 |

|

OD |

5.23 |

7.04 |

.356 |

58 |

104 |

Yes, the Wolverines’ Spring Training performance now indicates the W’s will finish 72 games out of first place, which I believe will be a major league record. After “the best Wolverine draft in a decade.” I said I couldn’t take finishing 66 games out. But I must be toughening up. I feel no worse looking at 72 games out. So why not trade Devers and Hayes? 72 games out, 80 games out – what’s the difference? Shouldn’t I, as an agent of God’s love, move those players to a better place, and make them available to owners who might still have a chance to win? Isn’t putting things to their best utilitarian use a fundamental principle of agape love, like not eating a brownie you sort of like so someone who loves them can have one?

It’s a good thing there are philosophers.

No, I actually mean that. In this case the philosopher in question is Gregg Twietmeyer, Associate Professor of Kinesiology at Mississippi State University. Do you think George Fox’s academic restructuring is hard to get used to? What if our philosophers taught in the Department of Kinesiology?

I suppose we shouldn’t laugh. They could easily end up in GF’s new Physician’s Assistants program.

Twietmeyer matters to this discussion because he just published on Christian Scholar’s Review a three part essay on “What Counts as Success in Sports?” I have studied every word, since I am no longer familiar with success in sports.

Twietmayer asks whether it is consistent with Christian love to value winning in sports. After all, to win you must make someone else lose. Your gain comes at another’s pain. So even at the simplest first level of analysis the loving Christian pauses, since we are told not to put ourselves above others, or be willing to buy our welfare with other people’s suffering.

Twietmayer points out that valuing winning can generate many layers of additional evils. We can succumb to the temptation to cheat, or intimidate opponents or undermine them. We can become obsessed with winning, devoting time and resources to it that should go to more productive or therapeutic behaviors, for our own benefit and others’. Even if we avoid vices ourselves, we can tolerate vicious behavior in our teammates to keep them on our side — and may even find ourselves conforming our standards to our teammates’ to fit in and be “part of the team.” We can end up admiring, valuing, and rewarding people for being winners when in many other aspects of life they are predators or parasites on the community’s welfare.

And then there are the losers. Not only do they suffer the pain of loss, their lives and souls can be corroded further by their own sense of inadequacy and unworthiness, both often fed by society’s disdain. They can lose jobs, or find their careers thwarted, lose relationships. Donnie Moore committed suicide after giving up Dave Henderson’s homer.

With all these toxicities, perhaps we should become competitive pacifists and utterly avoid any striving to win.

I mean, especially for a guy like me, who worked very hard to win in the spring drafts, what did it gain me? I go into Opening Day with my mouth full of the bitter ashes of Eloy’s shredded shoulder and a predicted last place finish a record 72 games out – all my hopes and plans in ruins. Why shouldn’t I convert to competitive pacifism, and play nothing but cooperative games where no one wins or loses?

———-

I think Twietmeyer might have taken Phil’s ethics class. He cites Alasdair MacIntyre before he gets around to Saint Augustine, which is the route I’ve watched Phil take many a time, and festoons the path with lots of other references.

Twietmeyer approaches the question carrying a tool: the notion that goods can be good without always being the same level of good. For example, Twietmeyer cites four “First Order” goods found in sports: Sportsmanship, Play, Skill Development, and Safety.

Safety doesn’t seem to point to playing sports. If you want to be safe you go sit down somewhere. You do NOT try to rob a home run by reaching over a fence, as Eloy did this morning, to his shoulder’s destruction (and probably to permanent damage to his career). I am unconvinced that the first order good of Safety has anything to offer to justify competing in a sport – or even participating in one.

Skill development is slightly stronger, since playing hard, and valuing “success”, can drive one to do the hard work of learning and practicing new skills. But Trietmeyer’s example – the diving header in soccer – is not convincing. In what other pursuit besides soccer will I ever use the skill of a diving header? Is a header even a good idea, since it is used to achieve something in soccer at the potential detriment of the rest of the player’s life, since headers are implicated in brain damage!

What skills does a baseball player develop that might be useful outside baseball? Perhaps basic physical fitness and cardiovascular exercise are goods, but frankly, baseball is not the best avenue to either of those things.

You can argue that baseball skills are valuable in the world of baseball, but we haven’t yet found a justification for baseball. So far all we’ve got is physical conditioning and safety, two goods which point more strongly to other pursuits.

In fantasy baseball the physical conditioning argument no longer applies, although safety is pretty much guaranteed. But skill development applicable to “real life” is all over the place. I’m writing right now, and Jamie will be very very soon. I’m learning to poke gentle fun at people, and (hopefully) to recognize better where the lines are between friendly fun and hurtful remarks. Jamie pointed out the development of my spreadsheet skills. I tried to bring together a four-way trade last week, and managed a still-impressive three way meeting that led to a good three-way trade. I write rules and learn to take criticism of them, and to be resilient enough to re-write them until everyone else is gasping for air.

All wonderful life skills. But they do not require winning.

Play is where Trietmeyer really gets onto something. We play EFL baseball for fun. Kids play real baseball for fun. Pro ballplayers say they have fun – although it’s hard to believe they do every game in a 162-game season. Fans have fun watching, and I hope (and dare to believe) that pro players have fun being watched and giving the fans something to watch. And it’s a simple fact, most of us usually have more fun playing together than solo.

And, it turns out, it’s even MORE more fun if we compete. “Why don’t we each try to win?” adds to the fun– as long as losing doesn’t ruin it completely. At least it has to be more fun to win than it is pain to lose, so each attempt is worth the risk and we are ready soon enough to try again. But it’s even better if the game is fun whether or not we win.

We put some extra effort into our league to achieve this. Like the spreadsheets I’ve shared, and this post I am writing, and the one Jamie is just about to let us see. We make up terms (like chulking) and memorialize events (Arismendy Alcantara!) and give out evanescent awards (La Tortuga, or Sherton Wimbert Rivero Apostel – whom Ryan just suggested I should trade to him! A league icon! Ha!).

That’s all good. Is it good without winning? I suppose. It’s been 8 years since I won. For some it’s been even longer. I am still having fun. Could I have as much fun without trying to win?

I don’t know if that’s the question. I think the question is “could everyone else have as much fun if I wasn’t trying to win?”

I have a son (NOT Ryan, as if you needed that assurance) who sometimes does not play to win. He plays to accomplish other things. He is less fun to play with when he does that. He might do something against his own competitive interest to help another member of the family. He is surprised when everyone complains about this, including the person he’s trying to help. He is undermining the game, undermining the fun, when he does that.

If we weren’t playing a competitive game, it would be a kindness if you would loan me your star outfielder for a year to help me deal with losing Eloy. But we have rules against being that kind of Good Samaritan. I won’t name any names, but when someone in this league offered me Marcel Ozuna for Ke’Bryan Hayes, and I looked into him and discovered Ozuna is on a 4 year, $11,000,000 contract, I did not take any offense. I admired the shrewdness of the move. He wasn’t hiding anything about Ozuna. He was competing. Ozuna would be a great fill-in for Eloy this year. He is likely to hit about as well and, despite his poor defensive reputation, is rated a 2.3 in the OF – an improvement over Eloy. Those are cleverly enticing features.

But this unnamed owner saw a chance to get Hayes, whose contract is 5 years and will total only $18,250,000 over that span, and who is likely to be as good as Ozuna – and maybe better — at a tougher position. That’s what he’s supposed to do. I’d have been at least faintly disappointed if he was offering me too sweet of a deal. And maybe he would have been faintly disappointed if I had, in my grief and without thinking, taken his deal and then regretted it for 5 years His competitive offer and my competitive response enhanced the experience.

So now we have a ground on which competing to win IS a good thing. It’s a conventional ground, by which I mean it depends on our mutual agreement: we will all compete fairly – within the rules without committing fraud – because we all want each other to compete, because it enhances everyone’s experience. This agreement almost guarantees that the experience will be positive for everyone, win or lose. We have transformed a formally zero-sum league into a strong positive-sum one.

Trietmeyer, working within a strict word limit, only hints at this. But it’s the heart of the case for competition.

The fourth first-order value depends on it: Sportsmanship. Trietmeyer helpfully grounds sportsmanship in loving our neighbor. I’d ground it also in loving our enemy. Competition is fun when played on level ground, with rules followed and enforced equitably on all. Cheating is not only practicing dishonesty, to our moral detriment, it is destroying the competition. It invites more cheating, because the cheater cannot complain about others cheating, nor even about others cheating in new and different ways. Cheating leads to lawlessness, and the game becomes a war.

But sportsmanship is more than obeying the formal rules. It is, as Trietmeyer points out, keeping the game in perspective, specifically the perspective that these are human beings we are playing with, each individually and lovingly created by God, to whom God has given the same life as we were given, and who matter far more than any game or any other value we might derive from the game. Sportsmanship is love, and doing nothing to an opponent we wouldn’t do to a son or a daughter.

I am not convinced that Trietmeyer’s second order values are really second order: Health, Community, and Lifelong Activity sound pretty fundamental to me. I would not sacrifice Health for Physical skills, nor community for them, either. I guess one might sacrifice community for love of neighbor: I’d leave my family rather than be complicit in slavery, for example.

But I, too, have a word limit – this is supposed to be fun – so I will not linger on Trietmeyer’s second order values. The important question is whether winning is even a third order value in sports.

Trietmeyer counts winning as a third order value because it has some intrinsic value, but that value should never be placed above the second and third order values. Winning is not worth sacrificing one’s health or safety. It’s not worth short-circuiting skill-acquisition. It’s not worth falling short of sportsmanship (loving the opponent).

But I wonder if it is a value at all. As Trietmeyer points out, winning has no bearing on God’s view of us and thus should have no bearing on our view of each other. Sherten Wimber Rivero Apostel should retain his value to me regardless of whether he ever makes it in MLB, or whether the Rangers are losers or winners while he’s on their team – as long as he is faithful to the higher order values.

So I want Sherten to try to win, because it’s necessary to many of the goods of the practice of baseball (including fantasy baseball). But in the end the winning only matters because of the way it feeds other things: play, fun, community, appreciation of the beauty of the sport, etc. If we could have all those things without winning (or losing) we would discard the winning. Like we do (hopefully) in a marriage. I am not trying to win my marriage with Melanie.

I will not be a competitive pacifist, nor will I do things contrary to the Wolverines’ competitive interests out of kindness to others. I’ll still try to win in the league even if my team is doomed to finish 72 games out of first. But I will try to remember winning is either not a value except by convention (we agree to pretend it is) or is a subsidiary value to everything else. If I grouse more than is entertaining, let me know, and I’ll modulate it to the needs of the group.

Final note: I might not have inflicted this long essay on you, if it weren’t for the fact that it serves as a warmup for another essay I want to write about Winning and Civility, possibly as a direct response to Trietmeyer. It will not be on this outline, nor will it refer more than obliquely to the EFL, but it will contain some of these ideas.

If you have any critiques, serious, fun, or both, I will be grateful.

This is wonderful, Ron. I have no substantive critiques, but found myself thinking often of how my parents taught us to play games as I was growing up. I think there might be a (pedestrian) essay there for me–unlike yours, which is anything but–but the teaching from my parents really boiled down to two pretty standard truths–you don’t gloat and you don’t pout when you win or lose.